-

About

- Biography

- Press

- Projects

- The Hitmaker

- PLANET C

- EVENTS / TOUR

- NRMedia

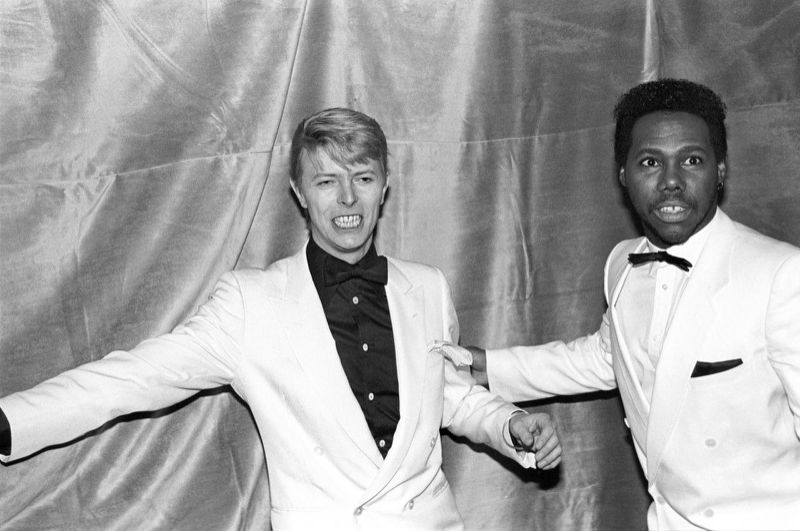

"David Bowie Changed My Life": Nile Rodgers Remembers His "Let's Dance" Collaborator

By Nile Rodgers

January 11, 2016

I had just come home this morning from visiting with my mom, who is suffering from a very serious illness. I'd only been asleep for an hour or so when somebody called and started saying, "What happened? What happened?" It took a while before the cobwebs cleared and I realized they were talking about David. To hear this, as soon as I woke up, was completely shocking.

When people ask me about the most important people in my musical world, one, of course, was my musical partner, Bernard Edwards, with whom I formed Chic. The other was David Bowie.

The Bowie I knew was a man who saw the world in the most unique way. Bowie would see the world we saw, and then he would see another world. The way he would describe something to me was in a visual way, even though we were interpreting it through music. "The Picasso of Rock 'N' Roll" – that's how I always referred to him. Any time I'd have to introduce him, I would call him that, and he would get a little flustered, because he thinks a great deal of Pablo Picasso, as do I. But I think that way of David Bowie – that's how extraordinary he was. And at the time in my life that I was persona non grata, when no one would work with me because of "Disco Sucks," this guy, who was considered one of the great, innovative rockers, picked a disco guy, who nobody wanted to work with, to collaborate with, and we wound up making the biggest record of his career, Let's Dance.

We met each other completely by accident – although I like to believe that there are really no accidents. He showed up at a place that he would never show up, and it was at a place where I would always show up. It was this after-hours club in New York City called the Continental. I knew the owners and would be there every night, and David was only there that one night. But that one night changed his life and my life forever.

I walked in the door of the club. Billy Idol and I were together, and Billy said, "Bloody hell, it's BOW-ie," which is how the English pronounce his name. He was so excited that Billy practically barfed when he said it: "BOW-ie!" But by the time he finished saying it, I was already next to David, talking. No one recognized him. This was 1982, the beginning of the whole club kid scene; everyone had spiky, big hair and looked wild. But not David. He looked incredibly natural. He looked like he could be the manager of the nightclub, as opposed to a patron. He was sitting all by himself, drinking a glass of orange juice. I walked right over and I introduced myself, and I said, "Hey, you live in the same building as all my best friends: Luther Vandross, Carlos Alomar…" – it was all the [artists who performed on Bowie's 1975 album] Young Americans. We had started out together; the guys who became the Young Americans were all my high school musician friends. And we started talking, and almost right away, we advanced the conversation from Young Americans to jazz. He was so enamored with jazz artists, from eclectic, avant garde to art-jazz artists to even what we'd call corny: very straight-ahead, Stan Getz and people like that. David loved it and appreciated it. The main reason why, he explained to me, was in those days, on the BBC, they just played everything; they didn't categorize it Blues, Rock, or Soul, or whatever. So David grew up with this incredibly open mind. From the moment we started speaking, we never stopped talking to each other; he and I, it was as if we were in a bubble and no one else existed. It was probably the most significant few hours of both of our careers, especially if you talk in terms of what was to come: the numbers, the units sold, and the influence. I know many people in the world who only have one David Bowie album, and it's Let's Dance.

I don't remember giving him my phone number, but I must have, because he called my house. When he called, I was having my house renovated at the time, and the workers kept hanging up on him. They thought, "There's no way David Bowie is calling Nile Rodgers." This was after "Disco Sucks," and the only artists I had worked with were my band Chic, Sister Sledge, and Diana Ross; so, to them, David Bowie – it was like the Pope calling. Finally, they said, "Mr. Rodgers, some jerk keeps calling up and saying he's David Bowie." I said, "That is David Bowie! Next time he calls, give me the phone!"

Luckily, he called again. And for the next few weeks, we went on an art search. We were looking for inspiration: What would this album, which would end up being called Let's Dance, sound like? We didn't know. So we just went out and started researching. This being way before the Internet, we actually went to the New York Public Library and to people's houses who had large record collections. We also went to record stores to go bin-diving. Because he didn't look like the freaky David Bowie – he looked like a normal guy; it was the beginning of the metrosexual look – we could go anywhere and everywhere. I was actually more recognizable than he was.

When we set out to do that project, he actually told me he wanted to make a commercial record, which I thought was bizarre, because I never thought of David Bowie as making commercial records. That's why I would call him the Picasso of Rock 'N' Roll: Because for him, making a commercial record was almost like an art project. It wasn't to get it to sell millions; it was almost like he wanted to make a commercial record just so he could feel what it felt like to do that.

That record, the amount of units we sold, was staggering. I've listened to him talk about it, and it really was uncomfortable for him, because it put him in a world that even he had never experienced before. And I get it. You go from being a very eclectic, avant garde artist that people had tons of respect for, where you're speaking to people on a higher level and… I don't mean to sound elitist, but the appreciation of David Bowie's music prior to Let's Dance presupposes a certain amount of sophistication on behalf of the listener. He was very, very on the cutting edge.

When we did Let's Dance, a lot of people don't realize it was an album of basically covers. He hired me as a producer to rearrange [songs] that had already been created. He gave me "Cat People," which he had done with Giorgio Moroder, and "China Girl," which he had done with Iggy Pop – there were already versions. But Bowie imagined another world that could be: Let's see what that might be like. He commissioned me to make a very commercial version of "China Girl" – although I thought he was going to fire me when I played him that riff [that opens the song]. I thought he was going to say, "That's the worst schlock I've ever heard." In fact, he smiled and said, "That's genius!"

David listened to me. I remember once explaining to him how, for me, as a black artist, it was very difficult for me to get hits, because we had fewer radio stations to expose our music. So to get attention, a technique of mine was I always started my songs with the chorus: "Ahhh, freak out!" and "We are family!" And then, of course, there's "Let's Dance." So when David gave me this award – for the ARChive of Contemporary Music – he said: "To my friend, Nile Rodgers: the only man who could make me start a song with a chorus."

The last time I heard from Bowie was a few years ago. I have a charity called the We Are Family Foundation, and after our 10-year anniversary [in 2011], the board decided they would honor me for my charitable work. They tried to figure out who would be the most appropriate person to give me that award, so they called David. At the time, he was sick; we could tell. So he did a film for me, and it was the sweetest, nicest, coolest thing ever. I've never to shown it to anyone outside of that room because it feels braggadocios – it's a film of him praising me. But it shows what kind of human he was. It was so loving. He was somewhat struggling to speak; you could tell he was ill. It had been reported that he had had a heart attack, so he would've just been recovering. It was just him showing me lots of love. And it meant so much.

This was a man who changed my life. When I made Let's Dance, Chic had broken up; I had had six failed records in a row. For me, at that young point in my career, I was just accustomed to having hit records. I couldn't understand making six records in a row and having them all fail, whereas prior to that, every record I made was a hit. I was all by myself, and David and I formed a partnership. It was the two of us against the world. I never felt more loved; I never felt like a person trusted me more. I did Let's Dance in 17 days, start to finish – it was the fastest record in my entire life. And when I say "finish," I mean mixed, done, delivered. Which is why you've never heard alternate versions; there's only one version of those songs. And that's because we were on the same wavelength. We'd finish a song and move right on. We'd do "China Girl" and go, "That's right!" We'd do "Modern Love" and go, "That's right!" We just zipped through it. That record is it.

After Let's Dance, every record I had was a hit. I produced INXS, then I did Duran Duran's "The Reflex," the biggest record of their career, then I did Madonna's "Like a Virgin." David Bowie put me back on the right path. He changed my life.

–as told to Lori Majewski

Read the full article HERE: https://www.yahoo.com/music/david-bowie-changed-my-life-nile-rodgers-180120507.html